How e-NG can turn energy from Net Zero to carbon negative, a conversation with Jens Schmidt

December 10, 2025

Reading time: 4 min

Cutting emissions is no longer enough. To truly restore climate balance, the next chapter of the energy transition must focus on pulling carbon back out of the atmosphere. This shift from “less carbon” to “negative carbon” defines the most ambitious edge of decarbonization, and it’s where TES is charting new ground.

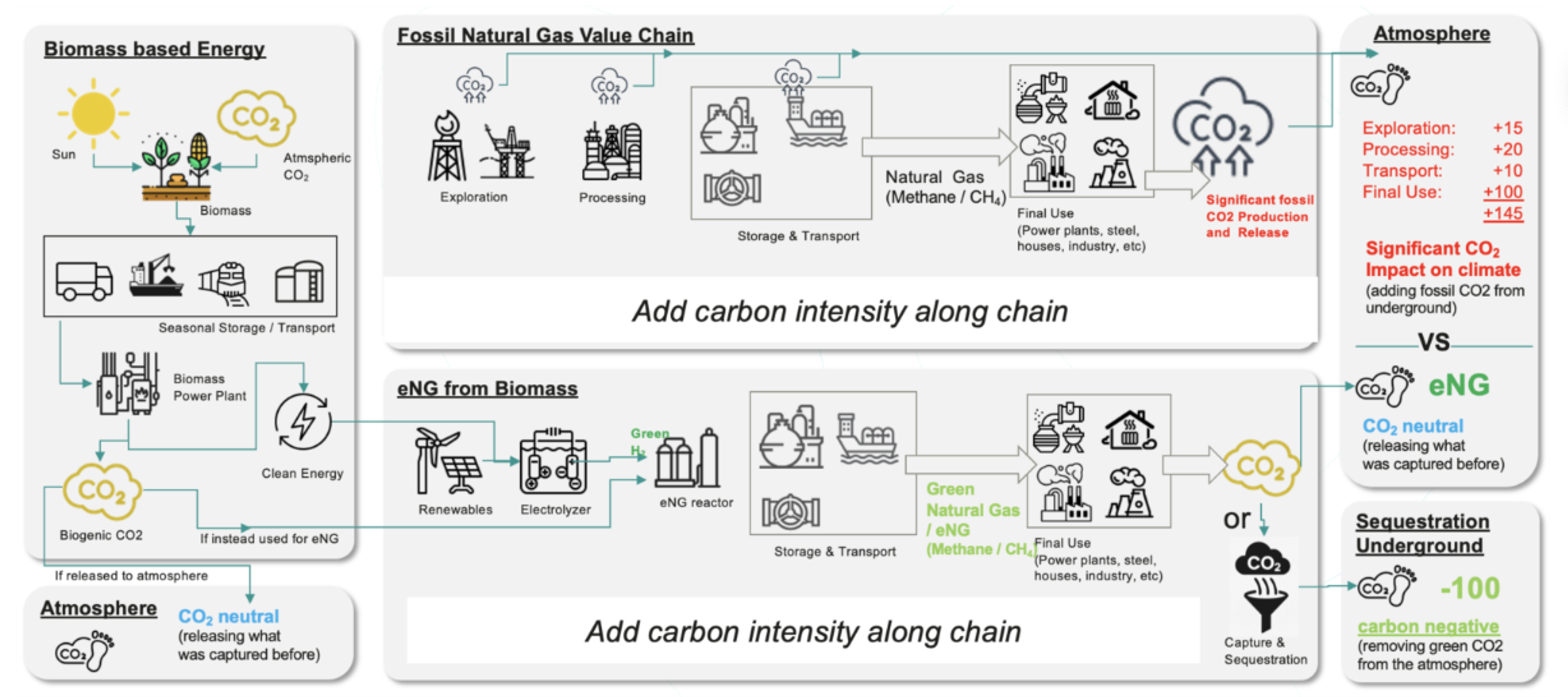

At the heart of this new frontier is e-NG (electric natural gas), not just a green alternative, but a catalyst for change. Produced by combining renewable hydrogen with biomass-sourced CO₂, e-NG works seamlessly within today’s gas infrastructure yet holds the unique potential to go beyond neutrality and become carbon negative when its CO₂ is permanently stored.

This represents a fundamental shift in how we think about energy. Instead of simply reducing emissions, e-NG enables energy production to become a process of carbon removal, actively drawing CO₂ out of the atmosphere. To understand how this works in practice and what it means for industry, we spoke with Jens Schmidt, Chief Technology Officer at TES, who explains the underlying mechanisms, the carbon accounting, and how carbon-negative e-NG can be deployed across industries.

Q: Jens, what allows e-NG to go beyond net zero and actually become carbon negative?

Jens Schmidt: To achieve a carbon-negative footprint, you need to permanently remove CO₂ from the atmosphere, not just avoid emitting it. That’s where CO₂ capture, transport and sequestration matter. If you capture CO₂ that nature has previously taken out of the air (what we call biogenic CO₂) and then store it underground instead of releasing it again, you create a negative footprint which generates a carbon credit.

Nature already captures and releases around 750 gigatons of CO₂ every year through photosynthesis using sunlight, about 400–500 gigatons of which come from biomass growing on land. The natural cycle remains climate-neutral because what it captures, it also releases. But human activity adds another 37–40 gigatons of carbon each year, tipping this equilibrium and accelerating global warming.

e-NG closes that loop. We borrow atmospheric CO₂ from the biogenic cycle, convert it into e-NG, transport it where it’s needed, and—if the CO₂ released during its use is captured and permanently stored—we remove that carbon from the cycle for good. Unlike biomass, which naturally decays and re-releases its CO₂, e-NG can achieve permanent removal. That’s what makes it carbon negative.(see graphic below to understand the CO₂ cycle)

Unlike other fuels such as ammonia, which can at best be carbon neutral, e-NG uniquely enables the transport of biogenic CO₂ from the point of capture to locations with existing sequestration infrastructure. It leverages the gas grid we already have, while requiring CO₂ capture and storage infrastructure at a few strategic, cost-efficient hubs.

How to harness natures’ CO2 cycle to offset human carbon emissions

Q: How does the carbon accounting work when part of the CO₂ is stored?

JS: We look at the full life cycle, from capture to end use. Each step has a carbon intensity: capturing CO₂ requires energy, electrolysis uses electricity, methanation consumes hydrogen.

If all of this is powered by renewable electricity and biogenic CO₂, the footprint of e-NG can be close to zero. Even in less ideal conditions, say, if grid electricity is used for carbon capture or gas liquefaction, e-NG remains well below the RFNBO threshold of 28 gCO₂e/MJ.

Now, when we sequester one ton of biogenic CO₂ at the end of the chain, that counts as a negative emission. So if we capture one ton of biogenic CO₂, turn it into e-NG, and in the value chain or end use release only 50 kg while permanently storing the other 950 kg, the result is a net footprint of –950 kg. The key is that the CO₂ we store came originally from the atmosphere captured via biomass, so we’re actively reducing the atmospheric stock.

Q: Which industries could benefit most from this carbon-negative pathway?

JS: Any industry that already uses natural gas can immediately cut emissions by switching to e-NG without changing infrastructure of process, just like biomethane.

If they already have in place or add carbon capture and sequestration at the point of use, they can go net negative. Beyond that, e-NG users can use these negative emissions to offset other parts of their value chain.

For example, a sugar producer might have unavoidable emissions from truck transport. By sequestering biogenic CO₂ after using e-NG, they can offset those emissions and even achieve company-wide net neutral ornegative footprints.

That’s what makes these credits so powerful, they’re not abstract or based on distant projects. Each ton can be tracked precisely from capture to storage, making e-NG-based removals transparent and verifiable.

Q: One major advantage of e-NG is infrastructure compatibility. Why is that so crucial for industrial adoption?

JS: Because time matters. Other hydrogen derivatives like ammonia or methanol require new infrastructure, pipelines, terminals, or shipping routes, and that takes decades.

Natural gas infrastructure, on the other hand, already exists globally, over 500,000 km of pipelines in Germany alone. e-NG is fully compatible with that system, so we can move renewable molecules at scale today, not in 2037.

The same applies to CO₂. Many biomass plants are located far from sequestration hubs. Converting their CO₂ into e-NG allows us to transport the CO₂ as energy contained in eNG through existing gas pipelines to places where it can be captured and stored after the eNG is used to replace fossil natural gas.

That’s the double benefit of e-NG, it’s both an energy carrier and a CO₂ carrier.

Q: Can you give a concrete example of how a company can integrate e-NG into its operations?

JS: A great example is our TES project in Florida. A local sugar producer there processes about five million tons of sugarcane a year. The leftover biomass, called bagasse, is burned to produce heat and power for their operations, releasing biogenic CO₂.

We’re planning to build an e-NG plant next to their site together. We capture that CO₂, use solar and biomass cogeneration powered electrolysis to make hydrogen, and combine both to produce e-NG. Because the facility is already connected to the gas grid, the e-NG can be injected directly and sold, for instance, to the cruise ship industry in Florida.

If the CO₂ is released at sea, that’s a carbon-neutral cycle. But if that same e-NG were used e.g. in a power plant with carbon capture or a reformer with carbon capture in a refinery, it would be carbon negative.

We’re developing similar projects in Spain, Sweden and Finland, with companies who own vast biomass/forest assets and biomass power plants. There too, by turning biogenic CO₂ into e-NG and sequestering it after use, the entire process becomes carbon negative.

Q: And what about the availability of biogenic CO₂, can the world really scale this?

JS: Yes. People often ask whether there’s enough biomass-based CO₂ to support large-scale e-NG production. The answer is absolutely!

Nature produces around 110 billion tons of biomass each year. That corresponds to 400–575 gigatons of CO₂ cycling through plants and soils annually, about ten times more than all human emissions combined.

So we’re not limited by supply, we’re limited by our ability to use what nature already provides. The beauty is that sunlight and CO₂ do the work for us, e-NG just captures that existing, renewable carbon cycle and turns it into a storable, transportable form of clean energy.

e-NG stands out as one of the only scalable energy carriers that can move from net zero to net negative without changing existing infrastructure. By combining renewable hydrogen with biogenic CO₂ and integrating sequestration at the end of its lifecycle, e-NG doesn’t just replace fossil gas, it actively removes CO₂ from the atmosphere.